By Ben Ames

BUFFALO, N.Y — Astronauts orbiting Earth in the International Space Station are in constant danger. As they spin around the planet, they must constantly dodge tiny chips of space junk.

Engineers at the U.S. North American Aerospace Defense Command in Colorado Springs, Colo. — otherwise known as NORAD — track the remnants of old meteorites and discarded satellite parts as small as cantaloupes. Yet even tiny grains of metal and rock could doom the spacecraft if they collided at orbit speeds that can reach 17,000 mph.

null

When astronauts live in a series of pressurized tubes, even a pinhole leak can be fatal. The challenge lies in the station's eight connected modules; a sudden drop in air pressure does not indicate which module might be leaking. Now a new software program will locate leaks before they drain off too much precious oxygen.

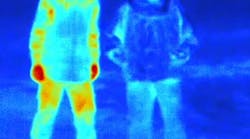

"It's not like a tire you can hold underwater to find a leak," says John Crassidis, associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the University at Buffalo in Buffalo, N.Y. "You might be able to hear where it is, or if there are fine particles in the air, you could see them getting sucked out."

In fact, astronauts find leaks today by starting in one end of the ship and closing all the doors. If the pressure in that module does not change, it must be sound. Then they move on to the next room. The last hatch they close is the escape capsule.

"That sequential process takes a lot of time," Crassidis says. But there's no time to waste. Faced with a 0.3-inch-diameter hole in the hull, an astronaut would have just two or three hours to locate and repair the leak.

Instead, Crassidis's software program analyzes the effect of the leak on the ship's motion. "If a leak is big enough, it acts like a thruster, generating torque, which can turn the ship or change its position in orbit," he says.

The space station's rockets automatically correct that movement. So Crassidis measures exactly how much the rockets fire, then works backward to calculate where the hole must be.

But there are additional hurdles. Natural turbulence such as solar wind also buffets the ship, masking the leak's effect. Also, there are an infinite number of solutions — a small leak positioned on the edge of a module could spin the space station as much as a large leak positioned in the middle.

"So we may get a unique solution, or we may get a short list," he says. "We could say go check modules 5, 7, and 10, or we could say exactly where to check inside the module. Either way, it's much faster now to find the leak."

NASA commissioned the software program through a $158,000 grant administered at United Space Alliance, in Houston. The software will run on mission-control computers at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston.

"No seal's ever perfect; there are always leaks somewhere," Crassidis says. "Ground control continuously monitors the air pressure, and our algorithm would kick in if it dropped beneath a certain level."

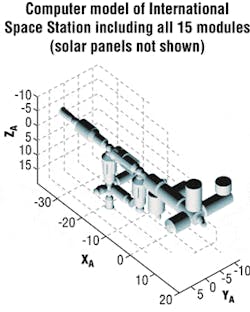

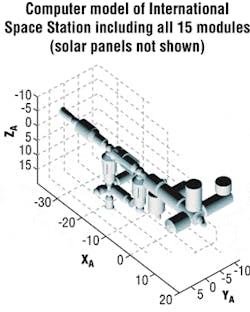

But the system will not help the astronauts aboard the space station today, because Crassidis's program is designed to protect the complete space station. The station was scheduled to grow from eight to 15 modules by 2004, but because NASA grounded its space-shuttle fleet after the Columbia explosion, that date has slipped to 2008.

null

Before teaching, Crassidis was an engineer at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. He was able to start work quickly on the project, along with professor Rao Vadali, now at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas, and doctoral student Jong-Woo Kim, now at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif.

Even if the space station can avoid collisions, Earth's orbit is still a crowded place, Crassidis points out. "There's a ton of space debris. Heck, Ed White's glove is up there somewhere." White was the first American to walk in space, during his mission aboard Gemini 4 in 1965. He dropped a silver glove in space as he re-entered the orbiter.

"NORAD tracks anything in space that's bigger than a small soccer ball. But any hole bigger than 0.4 inches would be catastrophic; the space station would collapse," Crassidis says. "This is kind of like the scenario of an object hitting the wing of the space shuttle, because that does happen. We're thinking about it, and we're making contingency plans."

As it is with the space shuttle, NASA's first priority is to avoid impacts before they happen. Finding and repairing leaks should be a last resort. "NASA is spending a lot of time making sure this never happens. Hopefully, they'll never have to use it," he says.