While the U.S. military has used remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs) since the Vietnam War with mixed results, recent combat action in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq has proven the utility of military unmanned systems, whether unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs), or unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs).

As a result, worldwide interest in unmanned systems is now surging as the U.S. UAV market finally shows real growth after years of talk and media hype. At least for the military-UAV market, there is little doubt about continued expansion, yet questions remain regarding the pace of this expansion, the level of UAV utilization, and the actual market size for "battle bots" as well as civil unmanned systems.

The budget figures reflect this trend. The Pentagon's fiscal year 2004 budget included around $1.3 billion for all UAV spending, compared to the $1.2 billion in 2003, $760 million in 2002, and $360 million in 2001. While significant, the 2004 figure pales compared with the nearly $6 billion earmarked for three manned fighter programs.

Overall spending on UAVs would exceed $2 billion in federal fiscal year 2005, which begins Oct. 1. The budget request calls for the U.S. Air Force to buy four Northrop Grumman RQ-4A Global Hawk high-altitude, long-endurance UAV systems at a cost of $360 million. The Air Force procured another four Global Hawks in 2004.

The Air Force would also receive nine Predator medium-altitude, long-endurance UAVs, worth $147 million, from General Atomics Aeronautical Systems Inc. in San Diego. The Air Force purchased 16 Predators worth $210 million in 2004 and 25 a year earlier valued at $139 million.

In February, General Atomics delivered the 100th RQ-1/MQ-1 Predator to the Air Force. The UAV is equipped with the Raytheon AN/AAS-52 multispectral targeting system (MTS) — a belly-mounted sensor ball incorporating electro-optical and infrared cameras and a laser designator.

The Air Force is set to begin acquiring the MQ-9 Hunter Killer Predator B, a more capable drone armed with the Hellfire missile. Mariner, a variant of the Predator B, has color and infrared cameras plus a surface-search radar. It is being pitched for the U.S. Navy's looming Broad-Area Maritime Surveillance (BAMS) requirement in opposition to a marine Global Hawk and a remote-controlled Gulfstream V business jet.

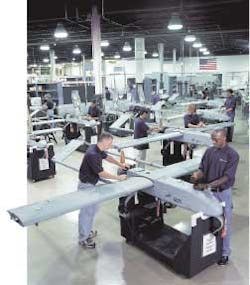

In fiscal 2005, the U.S. Army seeks four AAI Shadow 200 tactical UAV systems, worth $42 million, from AAI Corp in Hunt Valley, Md. AAI sees big things for its Shadow. The U.S. Army leadership cleared the RQ-7A TUAV program to enter full-rate production in October 2002, with the acquisition objective set for 83 Shadow systems. Currently, 41 RQ-7A systems are funded for the active Army.

A large chunk of planned spending in 2005 relates to UAV research and development. For example, the Air Force has earmarked $336 million for further Global Hawk-related R&D efforts, while spending on the Navy BAMS is pegged at $113 million. BAMS is billed as an adjunct to the manned Multimission Maritime Aircraft (MMA), planned to replace the Lockheed P-3C Orion anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft. The Navy could buy as many as 50 UAV systems for BAMS.

On the other hand, $710 million in fiscal 2005 would be for developing a Joint Unmanned Combat Air System (J-UCAS) for the U.S. Air Force and Navy. Compare this with the $176 million in 2004 and $54 million in 2003 spent to develop the J-UCAS predecessors, known as unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs). J-UCAS consolidates the separate Air Force and Navy UCAV developments. Research will accelerate, leading to an operational assessment in fiscal 2007–2009.

Meanwhile, the overall fiscal 2005 spending plan includes $3.2 billion for the U.S. Army's Future Combat Systems (FCS), which includes both UAV and UGV elements.

The Army plans to field a range of UAVs with the so-called Objective Force, including micro air vehicles (MAVs) and the Northrop Grumman RQ-8B Fire Scout vertical takeoff and landing tactical UAV system, which is similar to the RQ-8A being developed for the Navy.

Three types of revolutionary UGVs are envisioned: the United Defense Armed Robotic Vehicle (ARV), the Lockheed Martin Multifunction Utility/Logistics Equipment (MULE), and the iRobot Small Unmanned Ground Vehicle (SUGV), a pint-sized backpackable "bot."

A six-ton ARV version will have a missile-launching and medium-caliber gun turret supplying direct and indirect fire. It tips the scale considerably below the 70-ton M1A2 Abrams tank, the Army's current monster machine.

The 2.5-ton MULE includes three variants. Like the Army mule, one version will haul equipment for two infantry squads. Another variant will detect and mark land mines. Lastly, the Air Assault MULE will have "teeth," being armed with a rapid-fire gun and anti-tank weapon.

Pentagon spending on UAVs beyond 2005 is anybody's guess, but the "UAV Roadmap 2002" document says the U.S. military will likely invest more than $10 billion by 2010.

Today, the Pentagon has more than 90 UAVs in the field; by 2010, this inventory is expected to quadruple. "Taken as a whole, this technology offers profound opportunities to transform the manner in which this country conducts a wide array of military and military-support operations," the "UAV Roadmap" states.

The European market

On the export front, NATO has selected the Transatlantic Industrial Proposed Solution (TIPS) industry consortium to provide the Alliance Ground Surveillance (AGS) system, providing similar capabilities to the Air Force's manned E-8C

Joint Surveillance Target Attack Radar System, otherwise known as Joint STARS. The winning team bid a military variant of the Airbus A321 commercial airliner as the manned aircraft component. It will be paired with the Global Hawk.

Leaders of the European Aeronautic Defence and Space Co. (EADS) intend to be at the heart of Europe's UAV industry through initiatives such as its EuroHawk joint venture with Northrop Grumman. EuroHawk would replace Germany's Breguet Atlantic signals intelligence (SIGINT) aircraft starting in 2010.

EADS proposes a maritime surveillance variant of the RQ-4B EuroHawk as a possible replacement for manned German air force aircraft serving a similar role. The defense giant is also floating a concept for an imagery intelligence (IMINT) version of the RQ-4B for German air force purchase later this decade. It would carry a lightweight version of the European Stand-Off Surveillance and Target Acquisition Radar (SOSTAR).

The EuroHawk project is a pioneering effort in transatlantic cooperation. While European industry does not lack the skills required to develop UAVs, it has suffered from insufficient funding, placing it behind Israeli and U.S. UAV makers, says Dr. Tom Enders, head of the EADS's Defence and Security Systems unit. "We don't have the resources or the time to meet (European) requirements from scratch, so we must cooperate," says Enders.

In Europe, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Italy will invest most heavily in UAVs. France, Germany, and Israel already host some of the leading UAV manufacturers such as Elbit, IAI, Sagem SA, EADS, and Dassault Aviation, and are gearing up for the next generation of UAVs.

The European UAV market is expected to be worth around $6 billion over the next eight years, providing the world's second largest market for UAVs and unmanned-combat air vehicles over the coming decades. In the Pacific Rim, Australia is the first likely customer for a high-flying endurance UAV.

UAVs in civil airspace

Meantime, the U.S. Coast Guard is entering the UAV market with its Deepwater program, which includes two UAVs that will have to operate routinely in civil airspace. This suggests that UAVs will probably begin to penetrate the civil market through law-enforcement/homeland-security organizations like the Coast Guard.

NASA's Dryden Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base, Calif., has initiated a new project intended to enable high-flying UAVs to operate safely and routinely in civil airspace alongside conventionally piloted aircraft. It follows 2002–2003 flight testing of so-called detect, see, and avoid technologies that would permit manned and unmanned aircraft to peacefully co-exist over distant battlefields as well as above U.S. cities.

The research program is known as HALE ROA in the NAS (for High-Altitude, Long-Endurance Remotely Operated Aircraft in the National Airspace System). It brings together NASA, the Department of Defense, the Federal Aviation Administration, and six aerospace firms: Boeing, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, AeroVironment, General Atomics, and Aurora Flight Sciences.

The companies form the UAV National Industry Team, which strives to open the civil airspace to high-altitude, long-endurance remotely operated aircraft (HALE ROA) on a routine basis.

UAVs have been limited to restricted military airspace. Drones can operate in civil airspace, on a case-by-case basis, but such flights are tightly controlled to avoid conflict with conventionally piloted aircraft.

The primary issue of flying remotely or autonomously operated aircraft mixed in with conventionally controlled aircraft is one of flight safety — the need to guarantee that UAVs can fly with an equivalent level of safety as planes flown by on-board pilots. NASA will help develop the policies, procedures, and functional requirements that will ensure that HALE UAVs operate as safely as other routine users of the national airspace system. Such operations could begin as early as 2008.

The U.S. space agency officials initially are limiting their work to UAVs that routinely operate above 40,000 feet altitude. It will address other UAV operations later.

Ramon Lopez is editor of Unmanned Systems, the official publication of the Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI).