airport security

by J.R. Wilson

There is no such thing as airport security, in the singular. Rather, there are at least nine distinct areas of security concern at any airport, each with its own unique practices, procedures, techniques and equipment.

Even then, there are additional air safety issues involving aircraft and airspace security that are subjects for separate discussion.

At the nation's 429 commercial airports, in no particular order, authorities must contend with many passenger- and baggage-screening issues.

First, airlines must check individual passengers, their persons, and clothing as they attempt to pass from public to restricted areas on their way to their assigned departure gates. This began with walk-through metal detectors and hand-held wands, then expanded to explosives "sniffers" for some and, in a few locations, new scanners that can literally see through clothing. In the future, passengers may face biometric methods (authentication using individual behavioral or physical characteristics) such as iris scanners, retinal scanners, voice authentication, facial recognition, fingerprint identification, and hand geometry.

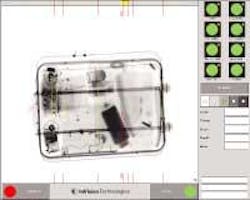

Second comes checking carry-on items, conducted concurrently with the above, but involving different measures. This generally involves X-ray scanning for all and explosives sniffers and even hand checks for some. A separate hand check of carry-on bags also has been instituted for randomly selected passengers at the gate itself, just prior to boarding.

Third, airlines must screen checked baggage going in the cargo hold. This has become one of the most costly and difficult measures as airports attempt to meet the "100 percent" rule ordered by Congress by 31 Dec. 2002. As the equipment is procured, installed, and brought on-line, checked baggage will be subjected to one of two machine screenings. The first type involve explosives-detection systems (EDS), which are extremely large and expensive machines (1,100 are scheduled for deployment this year), and explosives trace detection (ETD), which are smaller systems for low-activity environments or where airport space or structural limitations will not support EDS. About 5,000 have EDS machines been ordered for the nation's scheduled-service airports.

null

The pressure of achieving 100-percent screening of all checked baggage has led many in the airport and airline industry to request an extension of the congressional deadline. Newly appointed Transportation Security Administration (TSA) director Adm. James Loy says he appreciates those concerns, yet says he believes they are overshadowed by the terrorist threat. Loy made his comments last September in testimony before the Senate Commerce, Science and Transportation Committee.

"Therefore, I do not support a wholesale delay in the Dec. 31 deadline. We must deploy explosive-detection systems at all of our airports as soon as possible," he told lawmakers. "I will work with each airport to invest wisely in the solution that best meets the intent of the law. The Dec. 31 deadline enables us to focus our efforts. In a small number of airports, it may be necessary to push back the deadline for a modest amount of time, while temporarily putting in place other methods of screening checked baggage."

Fourth, airlines must screen non-passenger cargo, which often is the primary revenue source for airlines. Given that these tend to arrive at the airport in large containers, verifying they do not contain dangerous materials is a far more difficult task.

After that comes verifying the identities of airport, airline, and vendor employees who have access to secured areas inside and outside the terminal buildings. Identity badges are being upgraded to include magnetic strip or "smart card" chips with more information on the individual, which will be combined with some form of biometric verification. All of this comes after thorough background checks.

Sixth comes securing the public areas of the terminal buildings. A man armed with a knife, two handguns, and extra ammunition emphasized this need in July 2002 when he simply walked into the international terminal at Los Angeles and opened fire at the El Al ticket counter. The attack killed a ticket agent and a passenger, and wounded four others, before an airline security officer shot and killed the assailant.

Seventh comes defending the electronic component of airport operations against hackers or direct physical interruption. These areas include the air traffic control tower, ground control tower, and security facilities and systems themselves.

Next comes defending all structures, including parking garages, airline maintenance hangars and terminals, from car and truck bombs as well as human suicide bombers. This also includes protecting the airport perimeter itself from unauthorized penetration.

Ninth comes securing general- and business-aviation facilities. These two elements of private aviation comprise a significant element at many U.S. airports, far more so than anywhere else in the world. And the difficulties facing authorities are, in many ways, even greater, including concerns about arriving aircraft that generally would not apply to commercial flights. This also extends to the all-cargo air carriers.

It should be noted that none of these measures, individually or all in concert, would have stopped a single one of the 9/11 hijackers. Granted, they would have been relieved of their box cutters, but given the myriad ways in which one human being can kill or injure another, even with bare hands, nothing listed above would have seriously impaired their mission.

They flew openly, using their real names and with proper identification. Some might have been given special attention had the concerns of one or another government agency been shared by all, but even then, aside from some with visa violations, the majority would have been allowed to board. From that point, only changes in aircraft security, crew procedures and passenger awareness — all lessons taught by the suicide hijackings themselves — would have stood in their way.

Part of the federal effort to prevent such an attack in the future is mandated by an expansion of the 1997 Computer-Assisted Passenger Prescreening System (CAPPS), which directed the aggregating of individual traveler flight history and flagging potential security risks for more exhaustive baggage checking. CAPPS II extends coverage to all passengers, not just those checking luggage, and may be augmented by biometrics to ensure the person is who he says he is.

Which technologies are ready for use — and how best to use these technologies — is the subject of a study by the Aviation Security Biometrics Working Group, co-chaired by the newly created TSA and the Department of Defense Counterdrug Technology Development Program Office. Also represented are the FBI, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), National Institute of Justice-Technical Support Working Group, and the Office of National Drug Control Policy. Using data drawn from government, industry and academia, the group is scheduled to report to TSA by the end of November.

In addition to the biometric techniques already listed and available for implementation, if approved, researchers are still developing such feature identifiers as hand vein patterns, body coloring, lip patterns, dynamic signature verification, keystroke verification and even gait (movement) recognition.

Some technologies with long public histories, such as fingerprints, are undergoing revolutions in technology. Others that have been largely the province of science fiction are beginning to demonstrate remarkable capabilities.

null

For example, the potential for iris scans was demonstrated in March 2002 when the technology was applied to a photograph of an Afghan refugee girl that appeared on the cover of National Geographic magazine in 1985. The nearly two-decade-old photograph was compared to current pictures of women who claimed to be the haunting green-eyed teenager from the cover.

"It all got down to the eyes - that's what made the image so popular in the first place and that's where we had to look for answers," says Brian Armstrong, producer for National Geographic television. "We had more than one person claiming to be THE 'Afghan Girl,' so we had to be positive. It wasn't just the success or failure of the search that was at stake, but potentially the reputation of National Geographic.

"We needed an accurate, independent and conservative assessment," Armstrong continues. The experts at Iridian Technologies of Moorestown, N.J., spent several days reconfiguring their software to suit our specific needs and when Iridian finally said the eyes matched, we knew our search was over."

Even before biometrics become a significant part of the picture, however, passenger and baggage screening alone is costing billions of dollars to implement. Passenger and baggage screening involves more than 65,000 federal screeners and thousands of pieces of new (and often expensive) equipment, which costs airlines and passengers hours of wasted time. A passenger at a major airport may find the new security measures add up to two hours on the ground, even for a flight of less than an hour in the air.

As a result, throughput has become a major concern for airports, even as they seek to ensure public safety. While it may not be a significant problem to use any biometric on airport or airline employees, trying to process the public within the time constraints of a complex national aviation system is another story. Most systems require the subject to stop and take some prescribed action — looking at a camera, speaking a phrase, or placing a finger or hand on a scanner. All of those take some amount of time to process and return a result.

Loy says he and TSA officials are working to reduce the time spent on security checks and eliminate confusion and "unnecessary rules."

"As part of my plan to bring common sense into the aviation security area, I have charged my staff with taking aggressive steps to reduce the 'hassle factor' at airports and eliminate what I call 'unnecessary rules,'" he told the Senate committee, including ending the 16-year-old rule requiring ticket agents to ask if passengers have had control of their bags at all times. "These questions have not proven to enhance security. By eliminating them, we will speed up the check-in procedure so we can then more quickly move the passengers to the secure areas of the airport."

Despite website and other published guidance for travelers on what items airlines prohibit on aircraft, Loy says passenger screening last July alone intercepted 122,763 knives, 234,575 other types of prohibited cutting devices, 5,201 incendiary devices, and 228 firearms.

"From February 2002 through July, we have intercepted a total of more than 2.3 million prohibited items," he testified. "These numbers speak volumes about the public's continued confusion on what is prohibited from air travel under current circumstances."

Any security system essentially boils down to one of two formats — inclusion or exclusion. In the former, only those included in a known list of cleared individuals are allowed access; in the latter, only those on a known list of criminals or suspicious individuals are subjected to special attention. In the case of airport security, systems applying to airport and airline employees would be inclusive, while those attempting to screen the uncontrolled mass of passengers and airport visitors would be exclusive.

One effort to improve the application of advanced security systems to passengers is the so-called "trusted traveler" program, under which frequent travelers voluntarily register with authorities and receive smart cards that allow them to move quickly through the screening process. This already has been tested at airports in England and The Netherlands; Congress has authorized TSA to implement it in the United States as the "registered traveler" program.

"I am convinced that we can balance the needs of security with common sense for those who agree to register for this program and submit to a detailed background check," Loy told lawmakers. "Frequent fliers make up a large percentage of the air traveling public. By enrolling many of these frequent fliers as registered travelers, all air travelers can benefit.

"First of all, for those who register with the program and pass scrutiny, we will know more about them from a security standpoint than anonymous passengers who present themselves to our screeners at the airport," Loy continued. "This enhances aviation security. Secondly, by allowing the registered travelers to pass more quickly into the secured areas, this will ease congestion at the checkpoints and reduce overall waiting times for the registered travelers and for the traveling public that does not participate in the registered traveler program. Third, we will be able to reduce the hassle factor for those registered travelers. Finally, by implementing a registered traveler program we may be able to better utilize our airport workforce."

However, he added, TSA officials want to use the same type of card for registered travelers as they have proposed for the Transportation Worker Identification Card (TWIC) and that has been hampered by congressional orders not to proceed with any further plans to implement TWIC.

Overall, Loy warns, there is no "magic-bullet" technology that will handle all airport-related security issues, although TSA officials are supporting research efforts they hope will improve all levels of security in the next two to seven years, with a special near-term emphasis on the CAPPS II system and the development of "EDS Next Generation" technology.

In the long run, any security system is only as good as its weakest link — and with a system that relies on individual identification, that weak link is the impossibility of absolute certainty that any individual will never become a threat.

null