Lead-free RoHS on military electronics procurement

Worldwide environmental requirements to use lead-free solder continue to put the squeeze on military system designers who wish to avoid using lead-free electronics because of tin whiskers and other potential impediments to high-reliability electronics.

By J.R. Wilson

It has been nearly three years since the European Union (EU) ordered compliance with two sweeping environmental guidelines for electronics manufacturers:

- Directive 2002/95/EC on Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS), prohibiting the sale of electronic equipment in the EU containing lead, cadmium, mercury, hexavalent chromium, polybrominated biphenyls, or polybrominated diphenylethers; and

- Directive 2002/96/EU on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) policy for recovering and recycling products containing hazardous materials at the end of their useful lives.

Since then, China, Japan, Canada, and other nations have issued similar rules and individual European nations have added more restrictions to the EU RoHS and WEEE initiatives, including placing an end date on the current open-ended RoHS exemption for military, aerospace, and medical equipment.

In the U.S. and elsewhere, original equipment manufacturer (OEM) response to RoHS–especially within the military aerospace electronics industry–has been almost universally negative, with a specific focus on the ban on lead.

“Our experience in the U.S. in the past couple of years has been somewhat of a surprise at the slow pace of switch of customer demand to lead-free product. We’ve had a lot longer, bigger latent demand than we expected three years ago. When you look at what we are shipping now, there are a tremendous number of leaded products still going out,” says Bryan Brady, vice president of the Avnet Defense & Aerospace Business Unit in Tempe, Ariz.

“The caveat we often hear is the supply increasingly will move over at the OEM base to deal with lead free,” Brady explains. “Whether they want to or their customers are driving them to, that switch is happening and will happen and industry is dealing with all the points in-between. One of the questions I’m pursuing with industry is, if you had a warranted leaded product, would you prefer to use that–and the answer, especially from the defense side, is yes.”

Influence of COTS

Despite the mil-aero exemptions, the heavy reliance on COTS components from a commercial world whose major customers are not exempt has placed those industries in a de facto compliance environment. While the costs of conversion and compliance testing have been significant issues, the most serious objection involves the reliability of non-leaded solders.

As a result, industry began looking for ways to mitigate the risks identified with pure tin versus the traditional tin/lead solder and how to retain, at least in the short-run, an adequate supply of leaded components, especially to avoid a leaded/unleaded mixture on upgraded legacy systems. One approach already has resulted in the development of what has been described as a significant cottage industry: recoating RoHS-compliant components with lead. There are risks associated with subjecting devices to a third party, however, from exposing it to excessive temperatures to difficulty in covering all of the exposed areas of tin right up to the seating plane without damaging the device.

The EU RoHS guidelines “took the U.S. by surprise in that we thought we might have leaded configurations available for time immemorial–with embedded escaping influence or two different lines running in tandem,” says Tom Barnum, vice president-strategic accounts at rugged computer provider VersaLogic Corp. in Eugene, Ore. “I thought there would be an option to do both, either/or, and not that the ability to buy leaded components would be almost impossible. But manufacturers looked at this as a way to narrow their lines by eliminating the leaded configuration.

null

“We use COTS to accelerate time-to-market and achieve cost savings, but if we start futzing around at the component level to reball to a leaded finish, we are wasting time and dollars,” Barnum says. “For next-generation electronics applications, therefore, it just makes sense to move forward to RoHS compliance.”

Lead-free RoHS

To help address the lead-free element of RoHS, in 2004 the Aerospace Industries Association (AIA) in Arlington, Va., sponsored the Lead-Free Electronics in Aerospace Project (LEAP), which later brought in the Avionics Maintenance Conference (for airline representation) and the Technology Association of America (created by the 2009 merger of the American Electronics Association and the Information Technology Association of America). As a result, today LEAP is an international organization comprising not only aerospace OEMs, but also commercial end-users, government agencies, and all related market segments and supply chains.

“The international aspect isn’t so much looking at different regulations, but having the international players in the aerospace industry represented because we share a global supply base and do business with each other routinely, so we don’t want to have dueling standards,” LEAP Working Group member David Pinsky, a Raytheon Integrated Defense Systems Engineering Fellow and author of an AIA white paper on lead-free issues, explains.

“We didn’t take a compliance approach, but realized we would have to deal with a lot of materials coming into our system from sources over which we had no control and before we had answered all the technical questions we had,” adds Lloyd Condra, a Boeing Research & Technical Fellow who serves as chairman of the working group.

“Aerospace is out of scope for the directives and the legislation that resulted from it, so our concerns have been purely technical as our supply chains, which we don’t control, makes the change to comply with other markets and therefore are required to comply with RoHS,” Condra says. “That does impose some risks, such as tin whiskers and the reliability of solder joints on printed wiring boards when we use alloys other than traditional tin/lead.”

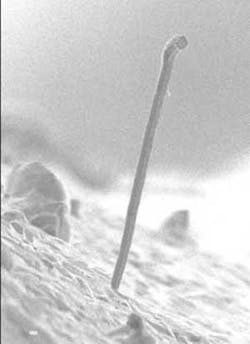

Tin whiskers

The concern over tin whiskers–small “hairs” that peel off the tin and cause shorts in circuit boards–is not only well documented, but fixed in law as well.

“In the 1980s, DOD (The U.S. Department of Defense) discovered this issue and put a prohibition on the use of pure tin in military and aerospace applications,” says Bill Palladino, quality compliance manager at Arrow Electronics Inc. in Melville, N.Y. “So the aerospace and defense industry views that risk as being far greater than the environmental risk associated with using a minute amount of lead in electronic components for the military. That is especially true when compared to the risk associated with tin whiskers.

“If you have a cell phone that is defective after a year and a half due to tin whiskers, it’s not a problem. But put that same component into a strategic defense communications system, which is intended to last longer and be more reliable, and you have a serious problem. You can’t use suspect parts that are contaminated by a real, documented phenomenon. To comply with RoHS, then, there would have to be an alternative other than pure tin. Some have developed palladium/gold and nickel silver alloys, but the vast majority are using pure tin, which the aerospace and defense industry will not embrace based on reliability issues.”

Cost also plays a major role in the decision-making process at the supplier level.

“From an economic standpoint, the problem is not enough demand for them to do that (employ alloys) given the higher expense,” says Bill Toumey, aerospace and defense vertical market director at Arrow Electronics. “The vast majority of cell phone and laptop manufacturers are perfectly content to use pure tin. And I’m not sure there is enough DOD business to motivate suppliers to produce along those lines (using other alloys).”

The LEAP program

The LEAP approach was to determine what rules would best enable RoHS compliance while still maintaining historically high standards and addressing the issues to aerospace. The top four of those issues are:

- long service lives, typically several decades compared to 2 to 3 years for cell phones, which lead market demand;

- rugged operational environments;

- repair of circuit cards at the assembly level, which almost no other industry does; and

- high consequences of failure, which must be addressed during the design and production phases.

To date, LEAP has produced four handbooks and three standards (available from AIA) designed to help RoHS exemptions in the industry deal with what is rapidly becoming market-driven forced compliance.

In addition, LEAP has worked in parallel with the Executive Lead-Free Integrated Process Team (ELF-IPT), formed by DOD to recommend government policy with regard to lead-free electronics. Two ELF-IPT publications–the “Roadmap for Lead-Free Implementation” and the “Joint DOD Lead-Free White Paper”–are among a variety of papers and analyses the DOD group–which also has FAA and NASA participation–has issued since its formation in 2005 to address military-specific issues stemming from RoHS.

“That group works hand-in-hand with the LEAP working group to develop policy recommendations to incorporate the result of the LEAP standards,” Condra says. “We’ve had pretty good success and the FAA, NASA, and DOD are working on consistent policies with each other and LEAP, leading various programs to adopt policies based on those standards.

“We’ve also had participation from other organizations around the world. It is surprising how much alike we all are across the globe. The folks in Europe and Japan and Canada are dealing with exactly the same issues and we’re all pretty much in the same place. Aerospace has been global for a long time and anything that happens is probably dealt with at about the same time everywhere.”

While LEAP steadfastly maintains it has no involvement in RoHS compliance–only the technical influence of such compliance by the global COTS supply chain–the vagaries of RoHS guidelines emerging from several governments, the lack of accepted standards, the absence of a certification process or entity and documented reliability issues in replacing tin/lead with pure tin solders and coatings all combine to create an environment that is simultaneously confusing, costly, technically questionable, may (at least in the short run) negatively influence U.S. competitiveness, and is potentially damaging to the maintenance of aviation safety and a stable, reliable national defense.

Work-arounds

At the same time, there seems general agreement that industry will find acceptable work-arounds, just as it did when, in 1994, then-Secretary of Defense William Perry ordered an end to strict reliance on milspec and a commitment instead to COTS to reduce costs and speed the insertion of technologies into military applications.

“There is no doubt this is a significant change for the industry and its customers, with a growing number of initiatives, not really in synch, that make things more difficult. Purely from an aerospace/defense standpoint, I think the government will continue to put the paramount requirement on quality and not add any risk to what they field to our men and women in uniform,” Palladino says.

“I don’t know what the ultimate answer will be, including a technology. The Perry report turned the industry around and there were worries then about the reliability of products coming from foreign countries,” Palladino continues. “But it all eventually settled out and solutions began to come out to maintain the reliability of the components they were manufacturing. And I’m confident somewhere in the industry we will come up with a way to maintain our stronghold on reliability for national defense, which cannot be waivered.”

Toumey of Arrow Electronics says he agrees–but with one major caveat: “Things do have a way of ironing themselves out, but a lot of things tend to happen on the way to that answer.

“Economics will dictate how manufacturers supply their product to market. Today there is some percentage of everybody’s commercial business that is still manufactured with lead because there are some applications that require lead. The economics there are increased minimums, maybe a higher price and, over time, those folks may find a different finish to get away from lead. So choice or availability from the open market suppliers is still there, but comes with a premium. Cost-to-quality is paramount here and the first thing the aerospace and defense industry must address is quality and risk mitigation. Nonetheless, at some point, we will come up with an alloy that will eliminate lead and deal with the tin-whisker problem.”

Economic realities

Such a process is not without its own costs, however–from development to proof of reliability, introduction into the manufacturing process, demonstration of RoHS compliance and, most importantly for mil/aero, risk management within legacy systems.

“It doesn’t matter what country you’re in; to convert all legacy manufacturing to lead-free would cost more than any government could bear. I’m surprised at the quantity of MilSpec that remains in the marketplace–almost a billion dollar market and still growing–15 years after that supposedly was brought to an end,” Brady notes. “Which demonstrates the strength these legacy systems have and the cost of qualifying products in a legacy system. So it isn’t just what it will cost, but who is going to fund it.

“If all available funds must go toward the actual procurement and not converting to COTS products, then my expectation is military customers will continue to buy leaded product, commercial or otherwise, as long as they can get it,” Brady continues. “I’m even seeing aftermarket solutions–not just solder dipping a lead-free product at a robotic plant, but remanufacturers offering versions produced with lead from the start. So I expect to see a leaded-product cottage industry for many years to come, driven by the military and others who have their own qualification schemes.”

Another current response to maintain the supply of leaded components include a significant “end-of-life” buy before suppliers shut down leaded production lines.

“The bottom line message, from our perspective as a key player in the supply chain and what we see in the OEMs, is the industry is getting a handle on dealing with lead-free and there are many viable solutions for those who want to continue to have lead in their systems from reliability concerns. There will be a cost factor for that; the question is what is the trade-off, depending on end-systems, prospects for the future, redesign qualification issues, etc.,” Brady says.

“If you are just trying to keep a legacy system alive and the switch would be costly, there are ways to do that without mixing inventories. If you are developing a system, however, it will be most cost-in embracing lead-free technology moving forward, unless reliability concerns trump those cost savings, in which case there are market solutions to get lead on your leads to resolve those.”

Military part numbers

With most suppliers finding it far less expensive to simply remove lead from their process rather than replace it with typically more costly alloys, especially when the vast majority of their customers have no problem with pure tin, a complication has arisen: part numbers that may or may not indicate whether a component is leaded or lead-free.

“The initial challenge is to figure out what you have in your systems and the supply chain protocols, especially those that have gone to supplier manufacturers and how they market their parts with respect to lead or lead free, which has not been a standardized practice. And it is not a trivial issue. Industry is coalescing on suppliers needing to change their part numbers between lead and lead free,” Brady says. “We’ve seen examples where a supplier has chosen to change their part number when they converted to lead-free and that they no longer make leaded products, they want to switch back to the original part number with the lead-free version.

“There is a lot of variation within the components industry on managing the switch and marking the parts so customers can track what they have and what they are getting. It has been incumbent on the consumer to institute processes to keep control of that and some have chosen to simply flow down purchase orders that say the supplier must fix it. Others have put in place component inspections or other reviews to determine what is and is not lead-free.”

Solder temperatures

Such inspections and tests, which can be costly, are a serious issue given the different melting points of different materials.

“When you have a circuit board with leaded and unleaded product, the reflow temperatures you use to solder the parts into place will differ because tin and lead melt at different temperatures. So you run a reliability risk by trying to reflow both alloys at the same temperature,” Palladino says. “But the prohibition on the use of pure tin–which is defined as more than 97 percent tin–is driven by the risk associated with tin whiskers, which has been the driving force behind not using pure tin RoHS-compliant devices. We see purchase orders from people like Lockheed, Boeing, and Raytheon, for example, which stipulate we are not permitted to send them devices with pure tin.”

Further complicating matters, as Norman Hartig, product introductions engineer at VersaLogic, notes, “there is no requirement for marking products as being RoHS compliant”.

Even properly labeled parts, however, do not address the real issue.

“When we buy subassemblies and components, there usually is some statement that they are RoHS-compliant. The fact it is or is not compliant, however, does not imply it is acceptable or unacceptable,” Pinsky notes. “What we have is a menu of options; we have tried to be data-driven and cautious so we don’t compromise our reliability as we implement solutions.

“Compliance, which we can only guess at since there is no law covering us, would clearly be different from what we’re doing if there were a law. Still, we anticipate the fraction of lead-free in systems will increase over time and, inevitably, our products will become more and more lead-free due to the changes in our supply chain. The commercial world already has made changes and moved forward (with respect to RoHS), but we have different requirements and so can’t just apply what they have done.”

RoHS a done deal

Despite the current industry exemptions, industry experts agree RoHS is a “done deal,” with an inevitability that must be accepted and addressed no matter what arguments may remain as to actual environmental necessity versus mil/aero reliability requirements.

“I don’t know anyone who is happy about the RoHS initiative–I know we aren’t–but we have no choice. If we are to control costs, then we have to use off-the-shelf components; by extension, our military clientele are going to have to move to a RoHS-compliant stance. Do they like that? No,” Barnum says. “The point where the military must have all leaded components is the point where COTS falls apart, at which point we would have to replace the entire supply chain and move back to a construct where the military does all their own assembly.

“We would not have the type of technology we have today had we not moved forward with the COTS initiative in the early ’90s,” Barnum continues. “The same is true about the introduction of RoHS–it’s just another step in the COTS timeline. The COTS market has gone to a lead-free configuration and COTS is defined as lead-free. If the military wants to continue to deploy the type of technologies we have, they will need technology from the commercial world. The military does not need RoHS-compliant missiles, of course, but given the mandate in the EU and the influence on consumer devices, there is simply no choice–where goes consumer electronics, so goes military electronics if we are to sustain the gains made through COTS.”

Meanwhile, governments will struggle to synchronize their RoHS regulations and organizations such as LEAP will continue to work with all involved parties to set global standards and seek resolution to the most serious issues.

“We believe we have accomplished more (with LEAP) than originally expected, but there is a lot yet to be done,” Condra concludes. “We believe the issues are becoming more severe despite the progress we have made. So there will be more recommendations made. There also may be structural changes in how the aerospace industry is set up to address this issue in the future.”